Residents of Okinawa, Sardinia, and Loma Linda, California, live longer, healthier lives than just about anyone else on Earth.

What if I said you could add up to ten years to your life?

A long healthy life is no accident. It begins with good genes, but it also depends on good habits. If you adopt the right lifestyle, experts say, chances are you may live up to a decade longer. So what’s the formula for success? In recent years researchers have fanned out across the globe to find the secrets to long life. Funded in part by the U.S. National Institute on Aging, scientists have focused on several regions where people live significantly longer. In Sardinia, Italy, one team of demographers found a hot spot of longevity in mountain villages where men reach age 100 at an amazing rate. On the islands of Okinawa, Japan, another team examined a group that is among the longest lived on Earth. And in Loma Linda, California, researchers studied a group of Seventh-day Adventists who rank among America’s longevity all-stars. Residents of these three places produce a high rate of centenarians, suffer a fraction of the diseases that commonly kill people in other parts of the developed world, and enjoy more healthy years of life. In sum, they offer three sets of “best practices” to emulate. The rest is up to you.

Sardinians

Out in the work shed behind his house in the village of Silanus, 75-year-old Tonino Tola emerges elbow-deep from the steaming carcass of a freshly slaughtered calf, sets down his knife, and greets me with a warm, bloody handshake. Then he takes his thick glistening fingers and tickles the chin of his five-month-old grandson, Filippo, who regards the scene from his mother’s arms. “Goochi, goochi goo,” Tonino whispers. For this strapping, six-foot-tall shepherd, these two things—hard work and family—form the bedrock of his life. They may also help explain why Tonino and his neighbors are a hot spot of longevity.

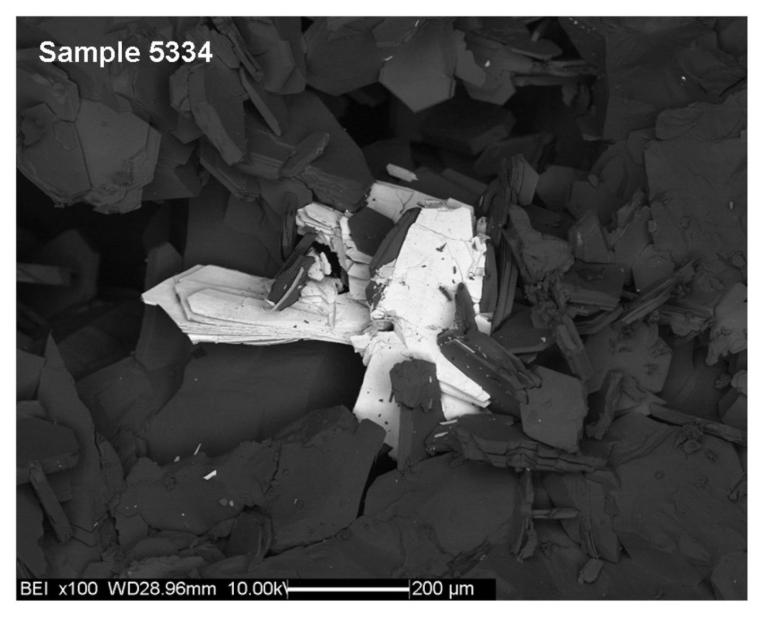

A community of 2,400 people, Silanus is located on the sloping fringes of the Gennargentu Mountains in central Sardinia, where parched pastures erupt into granite peaks. In a cluster of villages in the heart of a region called the Blue Zone by demographers, 91 of the 17,865 people born between 1880 and 1900 have lived to their hundredth birthday—a rate more than twice as high as the average for Italy.

Why the extraordinary longevity here? Lifestyle is part of the answer. By 11 a.m. on this particular day, Tonino has already milked four cows, split half a cord of wood, slaughtered a calf, and walked four miles (6.4 kilometers) of pasture with his sheep. Now, taking the day’s first break, he gathers his grown children, grandson, and visitors around the kitchen table. Giovanna, his wife, a robust woman with quick, intelligent eyes, unties a handkerchief containing a paper-thin flatbread called carta da musica, fills our tumblers with red wine, and slices a round of homemade pecorino cheese with the thumping severity of a woman in charge.

Like many wives here whose husbands are busy tending sheep, Giovanna shoulders the burdens of managing the house and family finances. Among Mediterranean cultures, Sardinian women have a reputation for taking on the stress of these responsibilities. For the men, less stress may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, which may explain why the ratio of female to male centenarians is nearly one to one in some parts of Sardinia, compared with a four to one ratio favoring women in the United States.

“I do the work,” admits Tonino, hooking Giovanna around the waist, “my ragazza does the worrying.”

These Sardinians also benefit from their genetic history. About 11,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers from the Iberian Peninsula made their way eastward to Sardinia. After several millennia the Bronze Age Nuragic culture arose on the island’s fertile coastal plains. When military powers such as the Phoenicians and Romans discovered Sardinia’s charms, the natives were forced to retreat deeper and deeper into the highlands. There they developed a wariness of foreigners and a reputation for banditry, kidnapping, and settling vendettas with the lesoria, the traditional Sardinian shepherd’s knife.

In their isolation native Sardinians became genetic incubators, amplifying certain traits over generations. Even today roughly 80 percent of them are directly related to the first Sardinians, says Paolo Francalacci of the University of Sassari. Somewhere in this genetic mix, he says, may lie a combination that favors longevity.

Tonino’s family’s diet is another factor. It’s loaded with homegrown fruits and vegetables such as zucchini, eggplant, tomatoes, and fava beans that may reduce the risk of heart disease and colon cancer. Also on the table: dairy products such as milk from grass-fed sheep and pecorino cheese, which, like fish, contribute protein and omega-3 fatty acids. Tonino still makes wine from his small vineyard of Cannonau grapes, which in this mountainous part of Sardinia contain two to three times as much of a component found in other wines that may prevent cardiovascular disease.

But with globalization and modernization, even remote Sardinia is changing. Cars and trucks have eliminated the need to walk long distances. Young people are more outward-looking and less traditional. Obesity, virtually nonexistent before 1940, now afflicts about 10 percent of Sardinians. “Children want potato chips and pizzas. That’s what they see on TV,” says Tonino. “Bread and pecorino are old-fashioned.”

One thing that hasn’t changed: the Sardinians’ dedication to family, which assures both support in times of crisis and life-extending care for the elderly. “I would never put my father in a retirement home,” says Tonino’s daughter Irene. “It would dishonor the family.”

For Tonino, the workday still includes a late afternoon trek to pasture his 200 sheep. Looking jaunty in his cap, coat, and leather gaiters, he strides through a narrow opening in a stone wall, counting his sheep as they follow him. When three sheep try to squeeze through, they knock over a section of the wall. With disquieting ease, Tonino hoists the heavy rocks back into place. Then he leans back on a rock outcropping and assumes the age-old role of sentinel, a routine he has performed for many decades.

“Do you ever get bored?” I ask. Before the words leave my mouth, I realize I’ve uttered a heresy. Tonino swings around, pointing at me, dried blood still rimming his fingernail, and booms: “I’ve loved living here every day of my life.”

Okinawans

The first thing you notice about Ushi Okushima is her laugh. It begins in her belly, rumbles up to her shoulders, and then erupts with a hee-haw that fills the room with pure joy. I first met Ushi five years ago at her home in Okinawa, and now it’s that same laugh that draws me back to her small wooden house in the seaside village of Ogimi. This rainy afternoon she sits snugly wrapped in a blue kimono. A heroic shock of hair is combed back from her bronzed forehead revealing alert, green eyes. Her smooth hands lie serenely folded in her lap. At her feet sit her friends, Setsuko and Matsu Taira, cross-legged on a tatami mat, sipping tea. Since I last visited Ushi, she’s taken a new job, tried to run away from home, and started wearing perfume. Predictable behavior for a young woman, perhaps, but Ushi is 103. When I ask about the perfume, she jokes that she has a new boyfriend, then claps a hand over her mouth before unleashing one of her blessed laughs.

With an average life expectancy of 78 years for men and 86 years for women, Okinawans are among the world’s longest lived people. More important, elders living in this lush subtropical archipelago tend to enjoy years free from disabilities. Okinawans have a fifth the heart disease, a fourth the breast and prostate cancer, and a third less dementia than Americans, says Craig Willcox of the Okinawa Centenarian Study.

What’s the key to their success? “Ikigai certainly helps,” Willcox offers. The word translates roughly to “that which makes one’s life worth living.” Older Okinawans, he says, possess a strong sense of purpose that may act as a buffer against stress and diseases such as hypertension. Many also belong to a Okinawan-style moai, a mutual support network that provides financial, emotional, and social help throughout life.

A lean diet may also be a factor. “A heaping plate of Okinawan vegetables, tofu, miso soup, and a little fish or meat will have fewer calories than a small hamburger,” says Makoto Suzuki of the Okinawa Centenarian Study. “And it will have many more healthy nutrients.” What’s more, many Okinawans who grew up before World War II never developed the tendency to overindulge. They still live by the Confucian-inspired adage “hara hachi bu—eat until your stomach is 80 percent full.”

And they grow much of their own food. Taking one look at the gardens kept by Okinawan centenarians, Greg Plotnikoff, a traditional-medicine researcher at the University of Minnesota, called them “cabinets of preventive medicine.” Herbs, spices, fruits, and vegetables, such as Chinese radishes, garlic, scallions, cabbage, turmeric, and tomatoes, he said, “contain compounds that may block cancers before they start.”

Ironically, for many older Okinawans this diet was born of hardship. Ushi Okushima grew up barefoot and poor. Her family scratched a living out of Ogimi’s rocky terrain, growing sweet potatoes, which formed the core of every meal. To celebrate the New Year, her village butchered a pig, and everyone got a morsel of pork.

During World War II, when U.S. warships shelled Okinawa, Ushi and Setsuko, whose husbands had been conscripted into the Japanese Army, fled to the mountains with their children. “We experienced terrible hunger,” Setsuko recalls.

Ushi now wakes every morning at six and eats a small breakfast of milk, bananas, and tomatoes. Until very recently she grew most of her food (she gave up gardening when she took a job). But her tradition-honored daily rituals haven’t changed: morning prayers to her ancestors, tea with friends, lunch with family, an afternoon nap, a sunset social hour with friends, and before bed a cup of sake infused with the herb mugwort. “It helps me sleep,” she says.

Back in Ushi’s house we’re finishing our tea. Outside, dusk is falling; rain patters on the roof. Ushi’s daughter, Kikue, who is 78 and finds little amusement in the attention her mother draws, shoots me a glare that I take to mean “you’ve overstayed your welcome.” (When Ushi ran away from home, she was actually fleeing an argument with Kikue. She packed a bag and boarded a bus without telling her daughter. A relative caught up with her in a town 40 miles (64.4 kilometers) away.)

Ushi, Setsuko, and Matsu take the cue and fall silent in unison. These women have shared each other’s fortunes and endured each other’s sorrows for nearly a century and now seem to communicate wordlessly.

What is Ushi’s ikigai, I ask—that powerful sense of purpose that older Okinawans are said to possess?

“It’s her longevity itself,” answers her daughter. “She brings pride to our family and this village, and now feels she must keep living even though she is often tired.”

I look to Ushi for her own answer.

“My ikigai is right here,” she says with a slow sweep of her hand that takes in Setsuko and Matsu. “If they die, I will wonder why I am still living.”

Adventists

It’s Friday morning, and Marge Jetton is barreling down the San Bernardino Freeway in her mauve Cadillac Seville. She peers out the windshield from behind dark sunshades, her head barely clearing the steering wheel. Marge, who turned 101 in September, is late for one of several volunteer commitments she has today, and she’s driving fast. Already this morning she’s walked a mile (1.6 kilometers), lifted weights, and eaten her oatmeal. “I don’t know why God gave me the privilege of living so long,” she says, pointing to herself. “But look what he did.”

God may or may not have had something to do with Marge’s vitality, but her religion has. Marge is a Seventh-day Adventist. We’re in Loma Linda, California, halfway between Palm Springs and Los Angeles. Here, surrounded by orange groves and usually blanketed in mustard-colored smog, lives a much-studied concentration of Seventh-day Adventists.

The Adventist Church—born during the era of 19th-century health reforms that popularized organized vegetarianism, the graham cracker, and breakfast cereals (John Harvey Kellogg was an Adventist when he started making wheat flakes)—has always preached and practiced a message of health. It expressly forbids smoking, alcohol consumption, and eating biblically unclean foods, such as pork. It also discourages the consumption of other meat, rich foods, caffeinated drinks, and “stimulating” condiments and spices. “Grains, fruits, nuts, and vegetables constitute the diet chosen for us by our Creator,” wrote Ellen White, an early figure who helped shape the Adventist Church. Adventists also observe the Sabbath on Saturday, socializing with other church members and enjoying a sanctuary in time that helps relieve stress. Today most Adventists follow the prescribed lifestyle—a testimony, perhaps, to the power of mixing health and religion.

From 1976 to 1988 the National Institutes of Health funded a study of 34,000 California Adventists to see whether their health-oriented lifestyle affected their life expectancy and risk of heart disease and cancer. The study found that the Adventists’ habit of consuming beans, soy milk, tomatoes, and other fruits lowered their risk of developing certain cancers. It also suggested that eating whole wheat bread, drinking five glasses of water a day, and, most surprisingly, consuming four servings of nuts a week reduced their risk of heart disease. And it found that not eating red meat had been helpful to avoid both cancer and heart disease.

In the end the study reached a stunning conclusion, says Gary Fraser of Loma Linda University: The average Adventist lived four to ten years longer than the average Californian. That makes the Adventists one of the nation’s most convincing cultures of longevity.

I meet Marge at the Plaza Place hair salon in Redlands, where she’s kept an 8 a.m. appointment with stylist Barbara Miller every Friday for the past 20 years. When I arrive, Marge is flipping through a copy of Reader’s Digest as Barbara uncurls a silver lock of hair. “You’re late!” she shouts. Behind Marge a line of stylists languidly coif other heads of hair, all in varying shades of gray. “We’re a bunch of dinosaurs around here,” Barbara whispers to me. “You may be,” Marge shoots back. “Not me.”

Half an hour later, her hair a cottony tuft, Marge leads me to her car. She doesn’t walk, quite, but scoots with a snappy, can-do shuffle. “Get in,” she orders. “You can help.” We drive to the Loma Linda adult services center, a day-care center for seniors, most of whom are several decades younger than Marge. She pops open her trunk and heaves out four bundles of magazines she’s collected during the week. “The old folks here like to read them and cut out the pictures for crafts,” Marge explains. Old folks?

Next stop: delivering recyclable bottles to a woman on welfare who will later redeem them for deposits. On the way Marge tells me she was born poor, to a mule skinner father and homemaker mother in Yuba City, California. She remembers the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, when she was just a toddler, and the aftershock that reached her family farm and sloshed water out of the animal trough. She worked as a nurse, put her husband through medical school, and raised two children as a doctor’s wife. Her husband, James, died two days before their 77th anniversary. “Of course I feel lonely once in a while, but for me that’s always been a sign to get up and go help somebody.”

Like many Adventists, Marge spends most of her time with other Adventists. “It’s difficult to have non-Adventist friends,” she says. “Where do you meet them? You don’t do the same things. I don’t go to movies or dances.” As a result, researchers say, Adventists increase their chances for long life by associating with people who reinforce their healthy behaviors.

At noon, back at Linda Valley Villa, where Marge lives in a community of retired Adventists, she treats me to lunch. We sit by ourselves, but a stream of neighbors stop by to say hello. Over tofu casserole and mixed green salad, I ask Marge to share her longevity wisdom.

“I haven’t eaten meat in 50 years, and I never eat between meals,” she says, tapping her perfect teeth. “They’re all mine.” Her volunteer work helps her avoid the life-shortening loneliness suffered by so many seniors—and gives her a sense of purpose, which imbues the lives of other successful centenarians. “I realized a long time ago that I needed to go out to the world,” she says. “The world was not going to come to me.”

I have a last question for Marge. After interviewing more than 50 centenarians on three continents, I’ve found every one likable; there hasn’t been a grump in the bunch. What’s the secret to a century of congeniality?

“Well, I like to talk to people,” she says. “I look at strangers as friends I haven’t met yet.” She pauses to rethink her answer. “Then again, people may look at me and wonder, Why doesn’t that woman keep her mouth shut!”

Article by By Dan Buettner, National Geographic Magazine, November 2005

-Main Photo on the top: Titolo: Famiglia dell’azienda di Corea durante il pranzo, Autore: Poddighe Elio, A cura di: Giraldi Francesca, Trudu Antonio, Sardinia Digital Library

-other photos from National Geographic Magazine November 2005